Kentucky's economy shows some progress mixed with struggles under Gov. Matt Bevin

Kentucky Gov. Matt Bevin seldom needs notes or a prepared speech at announcements such as the recent unveiling of UPS' $750 million expansion in Louisville.

Bevin beamed as employees and the shipping giant's executives burst into applause inside an aircraft hangar as he strolled to a microphone.

UPS' "extraordinary investment," Bevin said, would pay dividends for generations — thanks to the ripple effect of 1,000 high-paying jobs coming in the next decade and a half.

For the first-term governor who has made revving up Kentucky's economic engine a hallmark, appearances in Brandenburg for Nucor's new $1.3 billion steel mill, in Boone County for Amazon's $1.5 billion air hub, or in Georgetown for Toyota's $238 million investment have been part of a record-breaking run.

Bevin and his top cabinet appointees credit his administration's and the General Assembly's work to pass "right-to-work" legislation, his "cut the red tape" campaign to eliminate what he describes as overly burdensome regulations and a general pro-business approach for growing jobs in automotive manufacturing, aluminum and bourbon.

But economists caution that while economic development wins may hold the promise of new jobs and a boosted tax base in coming years, the state's fortunes are more tied to broader economic trends. Individual policies are a small piece of the puzzle.

"The global and national economy are the primary drivers of the state's economy. If the nation falls into recession, Kentucky will follow," said Michael Clark, an economist and interim director of the Center for Business and Economic Research at the University of Kentucky.

The center's most recent annual economic report highlighted positive news: More able-bodied people ages 25 to 64 are now employed across the state; the unemployment rate is down to 4.3%, a full point lower than it was when Bevin took office in 2016; and employment statewide has grown by more than 37,000 since late 2015.

Kentucky's median household income inched up 3.7%, to $50,247, but the state continues to trail the nation and several similar states in per capita income and median household income.

The poverty rate reached 16.9% last year, meaning more than 730,000 Kentucky residents were living at poverty level — $25,750 for a family of four. The poverty rates are even higher for minorities, with African American Kentuckians at 28.1% and Latino/Hispanic residents at 24.8%, compared with white people at 15.4%, according to data compiled by the Kentucky Center for Economic Policy.

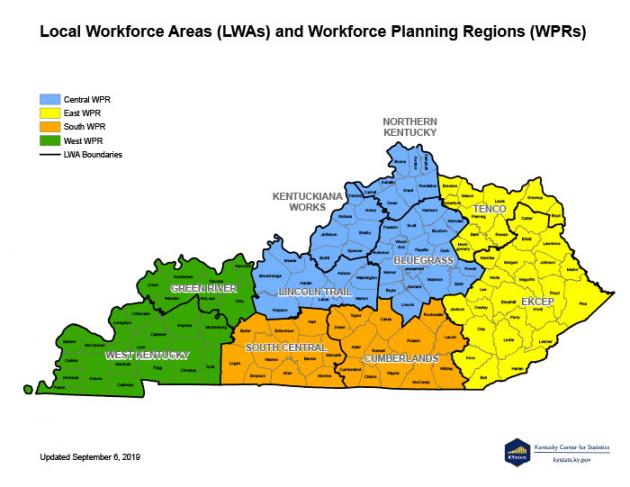

UK's yearly report also noted that while wage rates increased more than 2% last year, the state's urban areas disproportionately reaped the benefits with private sector wage growth and employment increases.

In the Louisville area, for instance, manufacturing jobs now average about $23 an hour, a boost from $21 an hour three years ago.

"For our region, it feels like a lot of momentum and a lot of growth," said Deana Epperly Karem, vice president of regional economic growth at Greater Louisville Inc., the metro chamber of commerce.

Challenges in outlying counties

Many rural areas, by contrast, continue to struggle, and Eastern Kentucky has been hit the hardest because of the coal industry's downturn. At the end of 2011, the state's 23 mountain counties boasted nearly 12,500 mining jobs. But that dwindled to 5,310 jobs by late 2015.

The latest census data shows mining payroll dropped to less than 3,700, which doesn't yet include 300 fewer miners in Harlan County suddenly out of work when the Blackjewel coal company filed for bankruptcy protection over the summer.

The poverty rate in the 5th Congressional District of Eastern Kentucky is now at 26.5%, which ranks as the fourth poorest district in the country, according to the Center for Economic Policy, a progressive, nonprofit group based in Berea.

"The reality is in Eastern Kentucky, we need to put 30,000 people to work," said Jared Arnett, chief executive of SOAR, or Shaping Our Appalachian Region, a nonprofit economic development corporation pushing for better broadband access and other improvements to connect residents to jobs.

"If we had a manufacturer that hired 2,500 people, it would be big news," Arnett said, but with "the depth of the challenges we're up against," the solutions have to extend across many industries and opportunities.

One company fueled by the demand for green, renewable power — battery cell manufacturer EnerBlu Inc. — announced plans to build a $300 million manufacturing plant in Pikeville in late 2017 and create 875 high-paying jobs.

But backers pulled the plug in February this year after financing fizzled, dealing another blow to the region.

One focus for SOAR has been growing remote call center opportunities that have delivered more than 3,000 full-time jobs. Though entry-level wages start at $11 and can go up to $16 an hour, professionals, such as nurses, teachers and college professors can make far more, Arnett said.

One company, Teleworks USA, has created hubs in eight communities where employees are hooked in to call center jobs and other positions. Several handle reservations for Hilton Hotels and U-Haul rental trucks, he said.

"Technology has disrupted every sector of the economy. We think it can disrupt poverty, too," he said.

Clashing over 'right-to-work'

One point of contention in Bevin's record centers on so called right-to-work, the 2017 law that bans requirements for workers to join a union or pay dues. Anti-collective bargaining forces insist right-to-work states benefit from higher wages and larger investments from companies that prefer to avoid union influence.

Union leaders and many progressive groups counter that there's no evidence right-to-work improves workers' pay and benefits.

Still, Bevin and his economic development team say right-to-work has been a huge factor in raising Kentucky's profile. The numbers of "leads," or companies searching for new sites to relocate or expand, jumped from an average of 40 per month to a high of 165 after the law passed, said Jack Mazurak, spokesman for the state Cabinet for Economic Development.

"It's added us to the forefront as a must-see state," Mazurak said.

He added that right-to-work is part of several elements prospective companies consider, but there's no question that it played a big role in driving a record list of new projects now in operation or in the pipeline.

Union leaders say "right-to-work for less" hasn't spurred new investment, and most new jobs added in recent years have come from companies that have existing operations in the state already.

"There's been no discernible increase in manufacturing jobs," said Bill Londrigan, the state president of the AFL-CIO, noting that companies that have announced big investments, such as such as Ford, UPS and General Motors in Bowling Green, also are union shops.

Londrigan questioned how the state can continue to count Braidy Industries' $1.3 billion aluminum rolling mill in Greenup County in its current tally of planned investments (with 550 jobs) when serious questions remain about whether the mill will ever be built.

"Braidy is still organizing its capital stack ... and until we see otherwise, it'll stay on" the list of future companies, Mazurak said. "Sometimes, companies aren't ready" and have to ask the state for extensions of time for projects receiving incentives.

Shrinking labor pool in Louisville

In places such as Louisville, the tight labor market has begun to weigh on companies in search of workers. At a job fair featuring 50 companies this month at Louisville's Cardinal Stadium, the traffic was light despite openings available for production workers, seasonal package handlers, maintenance technicians, machinists, welders and forklift operators.

A few dozen men and women, some in jeans, others clad in slacks and pressed dress shirts, carried resumes in folders from table to table, eager to talk to potential employers.

With the area's unemployment rate below 4%, the competition for workers is increasingly tough. “It seems like there’s a lot less people looking” for jobs now, said Ryan Rodgers, a recruiter with Kelly Services, which offers staffing and a variety of employment services.

A year ago, Kelly might have assembled a pool of 300 applicants for a company filling 150 call center slots in eastern Louisville. Now, Rodgers said, Kelly is hustling to find 200 to fill the positions.

Gig jobs, such as driving for ride-sharing companies like Uber and Lyft, may be compressing the numbers of potential candidates. People can to set their own schedules with those jobs, which has some appeal, Rodgers said.

“It’s made it more competitive (because) they can determine their own hustle.”

Despite the buyers' market for employees, finding the right job hasn't been a snap for Derien Guinyard, who came to the event dressed in a black suit and tie. He looked a little dejected as he slumped into a seat to fill out an application.

Most people wanted to pitch warehouse jobs to him, but the 24-year-old University of Louisville business administration graduate hoped to interview for something in information technology, with pay around $18 to $19 an hour.

He found few takers, and figured he may have to take a seasonal low-skilled job at a fulfillment center if he can't find something soon. Some employers have told Guinyard that he's short on experience for their specific IT positions.

“I wasn’t expecting something to fall into to my lap," Guinyard said, "but I was hoping if I put myself out there, maybe I’d have something by now."

Kentucky's economy under Gov. Matt Bevin

-37,606 — employment growth, last quarter 2015 to last quarter 2018

- 69% to 74% — the increase in the labor force participation rate for workers ages 25 to 64 between years 2015 to 2018. Nationally, the rate was about 76% in 2016, compared with 78.1% now.

-5.3% to 4.3% — the decline in the unemployment rate, January 2016 to July 2019, compared with the national rate of 4.7% to 3.5% during the period.

-$50,247 — state's median household income, a 3.7% increase between fall 2017 and end of 2018

-$22.3 billion — monetary amount of announced investments

---

Source: U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics and the Kentucky Cabinet for Economic Development

Date: 10-21-2019

By Grace Schneider

Louisville Courier Journal

Kentucky Press News Service